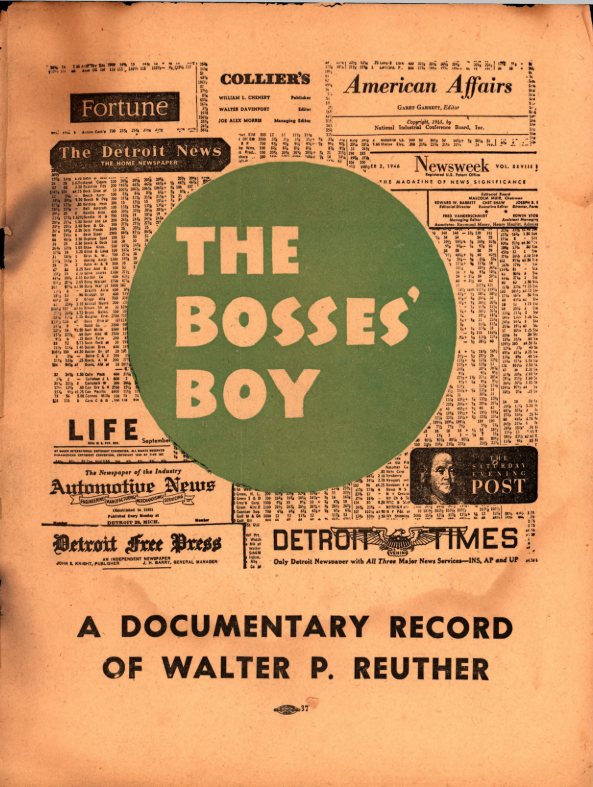

This pamphlet was issued in 1947 in the lead-up to a momentous UAW Convention. The UAW held an annual convention in those years, with election of the International President and Executive Board. Walter Reuther had narrowly been elected President at the 1946 Convention on an anti-communist platform, but had a minority on the Executive. Reuther’s opponents, known as the Thomas-Addes-Leonard slate attacked Reuther for his redbaiting, coziness with management, and a hypocritical approach to fighting racism. The pamphlet was issued in the name of a “Rank and File Committee” and signed by 27 Presidents of UAW Locals and 2 other Local leaders.

The Bosses’ Boy is mentioned in a number of books and articles.

From Roger Keeran’s useful book The Communist Party and the Auto Workers’ Unions:

The Thomas-Addes forces presented their case to the membership in a 24-page pamphlet entitled The Bosses’ Boy and in a little periodical entitled FDR. Sigmund Diamond, Irving Richter, and other left-wing staff members wrote The Basses’ Boy, and Carl Haessler edited the first issues of FDR, whose acronym insiders jokingly interpreted to mean “F**k Dirty Reuther.” While scoring Reuther’s desire to link wages and productivity, the low wages in Reuther’s GM division, the president’s neglect of minority representation, and his constant redbaiting, these publications also made exaggerated claims of Reuther’s support of speedup, which the union president easily refuted. Less refutable was the voluminous documentation in The Bosses’ Boy that the greatest praise for Reuther’s anti-Communism came from the most anti-labor forces in the country—the Hearst press, the Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, Gerald L.K. Smith, and Harold Story.

Roger Keeran, The Communist Party and the auto workers’ unions (New York, NY: International Publishers, 1986) pp 281-282

Nelson Lichtenstein, in his biography Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit mentions The Bosses’ Boy in a footnote. Lichtenstein is more dismissive of the document than Keeran, and does not directly address any of the evidence cited in it.

Irving Richter and Sigmund Diamond wrote most of “The Bosses’ Boy.” By all accounts, the publication enraged Walter Reuther: stretching their evidence, the authors accused Reuther of favoring speedup, maintaining an alliance with Robert Taft, and failing to fight discrimination against African-Americans in the UAW.

Nelson Lichtenstein, The most dangerous man in Detroit: Walter Reuther and the fate of American labor (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1995) p. 504.

Clayton W. Fountain’s Union Guy is his “own tale of how I came to Detroit reaching for fat paychecks and got hit in the face with a depression; of how I joined a union in selfdefense and was sucked into the Communist party; of how I walked out of the party because it violated my freedom, and then helped to clean a lot of Commies out of my union.” Fountain says of The Bosses’ Boy:

From late July until early October, the Commies threw everything but their hammer and sickle at Walter Reuther. Acting through the Addes-Thomas-Leonard caucus, they unleashed a campaign which ranks among the bitterest in American labor history. Here are some examples:

With the hired brains of a three-hundred-dollar-a-week press agent, they published a twenty-four-page magazine entitled The Bosses’ Boy. This document endeavored to prove that Reuther was the darling of American big business. We laughed that one off.

Clayton W. Fountain, Union Guy (New York: The Viking Press, 1949) p. 208.